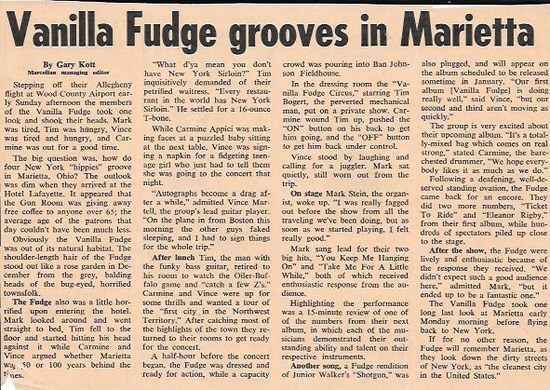

More About Vanilla Fudge

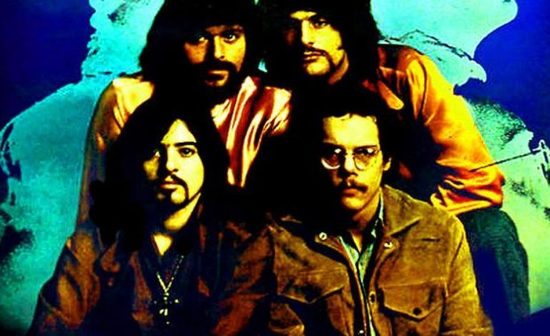

To put it mildly, I was persona non grata when they saw me at the airport. The airplane carrying Vanilla Fudge was just landing, and members of Marietta College’s student-run Social Planning Board were furious that I might rain on their parade. The leader of the board minced no words, “We booked this group. We’re meeting them at the gate. You’re not invited.” Another member chimed in, “We don’t want you. We don’t need you.” A third member capped it off, “If you want an interview for the school paper you can meet them at the baggage claim. But before then Vanilla Fudge is ours. All ours.” It wasn’t the first time I’d felt the wrath of the Social Planning Board. They were still fuming that I’d wangled my way into interviewing Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels. And ended up shooting hoops with Frankie Valli of the Four Seasons. Not to mention my unauthorized interviews with the Temptations and James Brown. The Social Planning Board believed strongly that everything concerning the social life at Marietta College be done by the books. Permission to hire entertainment. Permission to advertise. Permission to meet and greet. My off-the-cuff, spontaneous, side-door approach to getting a story was pure anathema. Nonetheless, I stepped far away and watched as the members of the Social Planning Board, dressed spiffy in their tweed sport coats and beige ruffle dresses greeted the paisley-clad, hipper-than-hip rock band. I couldn’t hear what they were saying but I could tell that the musicians, forefathers of sixties psychedelia, were trying hard to break free from these human relics from the fifties if not forties. When Vanilla Fudge, alone now, reached the baggage area they seemed somewhat relieved when I approached them and identified myself as a reporter for the college newspaper. It’s not that the group was dying to give an interview, they were just relieved to meet someone more on their wavelength; my long hair, Fu Manchu mustache, bellbottoms, and a blanket-jacket that smelled of pot. Instead of me asking questions, I was bombarded by the rock group, “Where the hell are we?” “Did we land in the Twilight Zone?” “Tweed sport coats?” They were relieved when I confirmed that they were not hallucinating. Indeed, in 1968, Marietta, Ohio was still in a time bubble. Conservative people. Conservative clothing. Conservative attitudes. While other college campuses were rioting over free speech, the most pressing topic at Marietta College was what sorority sister would win Queen of the Homecoming Weekend. When the band was about to head to its hotel, I said goodbye, only to be grabbed and shoved into their car, “You’re not going anywhere. You’re coming with us.” And that’s the way it was for the entire day. Me and Vanilla Fudge at the hotel restaurant, with the Social Planning Board sitting two tables away shooting darts my way. Me and Vanilla Fudge in their suite, listening to a reel-to-reel rough mix of their next album that included a mind-blowing version of one of my favorite all-time songs, “Shotgun” by Junior Walker and the All Stars. Me and Vanilla Fudge at a local pizza parlor with me trying to explain to fans that no I can’t sign autographs because I’m not part of the band. There was one awkward situation. The night of the concert, one of the group members (name omitted) approached me nervously, “I left something illegal in my jacket pocket hanging in the dressing room. There’s a cop standing guard outside. I’m worried that –” He didn’t need to explain more. I slipped past the guard, retrieved the substance from the jacket pocket, and flushed it safely out of harms way. Then I went back to the auditorium and witnessed one of the best rock concerts my young eyes had ever seen. The highlight? Vanilla Fudge introduced a new song, “It’s our rendition of Jr. Walker’s ‘Shotgun.’ And we’d like to dedicate it to our good friend Gary Kott.”

BONUS MORE ABOUT

In 1969, I was a destitute but nervy college senior, managing editor of my dinky college newspaper (the Marcolian, Marietta College, Marietta Ohio). My major skill as a journalist was wangling my way into places I shouldn’t be via flashing my flimsy cardboard press pass or concocting ruses, gaining interviews with James Brown, the Temptations, entrance into the U.S. Open, backstage to a Woody Allen play, and, most ignobly, the private office of Bill Graham at the Fillmore East. It was an inauspicious introduction. My friend Smitty and I ventured to New York City with no money, stuffed our belongings into a locker at Grand Central Station, bummed food off the Hare Krishna at their East Village temple, spent the first night in an all-night porn theatre on Times Square, and the second in the crash pad of a local Hells Angels chapter. The next night we were standing outside the Fillmore ruing that we couldn’t afford even the cheapest seats to see The Chambers Brothers. “No problem,” I said confidently, and proceeded toward the stage door, flashing my press pass to the beefy security guard who not only didn’t glance at it but shoved me into some garbage cans. Employing a strategy I’d used several times before, I waited patiently for the guard to be distracted by a disturbance, dashed through the stage door, and ran down a hallway, hotly pursued by the furious security guard. Desperate, I lunged for a door knob, twisted it, and there he was, Bill Graham at his desk doing paperwork. I have no idea what I said to him, but by the time the security guard grabbed me by the neck, Bill Graham was laughing so hard he instructed the guard to let me go. Alone with the famous impresario, we shot the breeze about all things sixties, Vietnam, draft-dodging, Country Joe and the Fish. Finally, Bill Graham asked me, “Want to see the Chambers Brothers?” I confessed, “I don’t have a dime.” Appreciating the honesty of an accomplished but amateur hustler, Bill Graham pointed to a door outside his office, “That leads to the auditorium, go find a seat.” Appreciative, I headed that way until I realized, “My friend Smitty’s waiting outside. He doesn’t have a dime either.” Now a bit irritated, Bill Graham paused for a moment, then shrugged, “Go get Smitty.” I rushed down the hallway toward the stage door, opened it, yanked Smitty inside, and headed fast for the auditorium door, not losing a step when the security guard smacked me in the back of my head.

Please continue to: https://garykott.com/more-about/