More About “The Six-Day War”

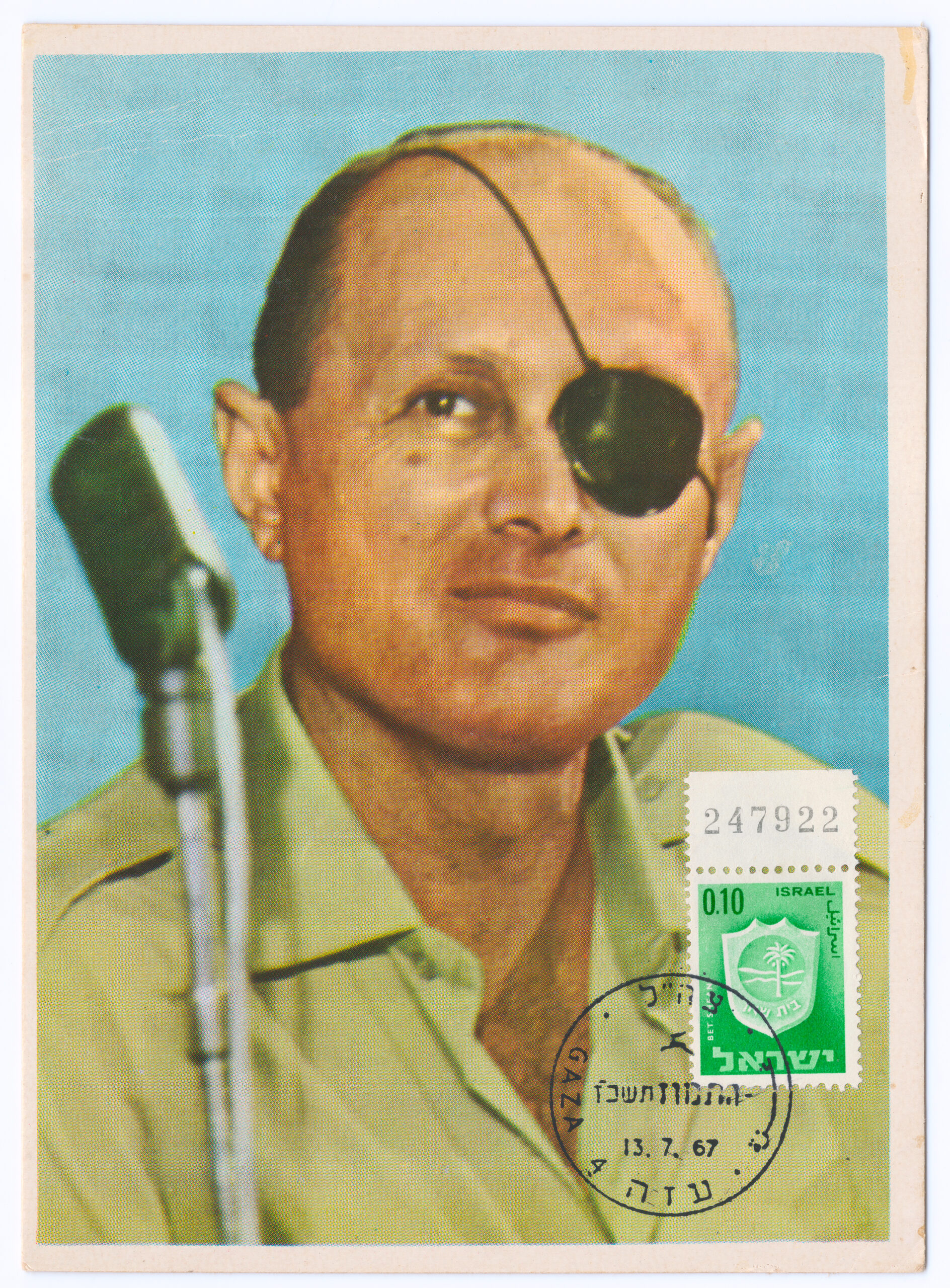

Guess who I bumped into, literally, shoulder smacking shoulder, he, racing in one direction at Lod Airport me heading to the baggage claim, his bodyguards scurrying to keep up with him, someone clueing me in as if I didn’t recognize that famous eye patch I’d seen in countless newspaper photographs, “Moshe Dayan. You just collided with Israel’s Defense Minister.” It was the first of two encounters I had with Moshe Dayan, the second ten days later in the lobby of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, an omen, I took it, a sign telling me to skip my final semester of college, move to Israel, and become a newspaper reporter for the Jerusalem Post. It was now five months since the end of 1967’s Six-Day War in which the Israeli Army succeeded in defeating a coalition attack by Egypt, Jordan, and Syria. Postwar Israel, trying to restore interest in tourism, offered bargain-basement deals for Americans to come visit the battle-scarred country. It was an eye-popping experience. Until then, I’d only seen images of war in books and on television, however, now, as our plane approached the airport, I could see bombed-out remnants of battle. We disembarked to friendly but stern guards ushering us quickly into a room for passport inspection, luggage collection, and a swift march into a waiting transport bus. This would be the beginning of many-to-come cultural flabbergasts. Backstory: Growing up with a Jewish grandmother still in trauma from her life in Germany, I was firmly instructed by my parents to park three blocks away when I visited her in my used Volkswagen bug. So, what was the first sight I saw when the tourist bus pulled away from Lod Airport? A Volkswagen dealership. Welcome to modern Israel, the horrors of the holocaust taking a back seat to the imminent danger posed by surrounding Arab nations. It seemed unfathomable to learn that young Israelis, choosing to emigrate to another country in hopes of improving their career options, didn’t choose America, didn’t choose England, they chose, of all places, Germany. There were so many flabbergasts yet to come. Growing up in New Jersey there was always the threat of violence, street fights, playground fights, one-on-one fights, however, mere child’s play compared to living in Israel. While visiting the Jordan River I was startled by a sudden eruption of machine gun fire around the bend. The next day in Hebron, Israeli soldiers attacked a group of armed Arab militants while other soldiers rushed us onto a bus. On our visit to the Golan Heights, site of the fiercest fighting during the Six-Day War, we were warned to stay on a thin path since live mine fields flanked us on either side. Next, we were warned not to touch abandoned Russian tanks, red stars still visible on their turrets. Finally, we were warned not to disturb Arab battlefield artifacts strewn about massive, indestructible concrete bunkers built into the mountain, cannons still aimed at defenseless Israeli villages below. Then there was my impromptu visit to the Gaza Strip, a volatile area of occupied territory that was strictly off-limits. Curious, I asked several taxi drivers if they would take me there, getting not one taker until I approached an intimidating driver who told me to hop in. He swore me to secrecy then took off on our sixty-mile journey. The driver warned me about the inherent risk of driving into this dangerous tinderbox but put me somewhat at ease by divulging that he’d been an infantry colonel in the military defeat of Gaza. Once inside the city limits, I was mesmerized by the horrid destruction of war, crumbled buildings, streets strewn with splintered furniture, walls tattered by bullet holes. A group of Arabs spotted us and made an advance, turning back only when the driver pulled from his waistband a menacing black handgun, aimed it at the crowd, and threatened to shoot. Then the driver calmly announced to me, “Gaza tour over,” and sped me back to my hotel. The country’s stress level was raised the day after Christmas with news that Arab terrorists fired eighty rounds and hurled hand grenades into an El Al flight to New York waiting to take off at the airport in Athens, Greece, killing one Israeli and wounding others. Learning that the terrorists were based in Lebanon, Israel retaliated two days later by landing commandos in Beirut and inflicting destructive mayhem. Was war about to break out again? For the Israelis this threat was something they’d grown accustomed to, for the tourists it was a time of extreme anxiety, for me it was my rallying cry. I jumped into a taxi and sped off to the offices of the Jerusalem Post. Impassioned with an intense pride for my Judaism and brimming with a newfound love for the State of Israel, I approached the receptionist with a fervor, “My name is Gary Kott. I’m the Managing Editor of my college newspaper, The Marcolian. I’d like to speak with the Editor about a reporting job on his newspaper.” The receptionist, half annoyed, half amused, told me that, “Seeing the Editor without an appointment is impossible.” I answered, “Then I’d like to make an appointment.” She toyed with me by glancing at her calendar, “You’re in luck. The Editor just had a cancellation. Eight a.m., Tuesday, March 25, 1983. See you back here in sixteen years.” I was adamant, “No problem. I’ll wait.” And I took a seat in the lobby, sat there for three hours, until, finally, the receptionist dialed a number, spoke to someone, then announced, “The Editor said to come right up.” Inside the office of the Editor, I went straight to business, impressing upon him my sincere desire to leave America, to live in a country that actually stood for something, railing against the War in Vietnam, pledging my loyalty to the Israel military, and, most important, promising to be a no-nonsense journalist for the Jerusalem Post.” The Editor, non-plussed, asked one pertinent question, “What makes you think you could get a story that my reporters couldn’t?” I came back strongly, “Yesterday, I made it into the Gaza Strip. I didn’t see any of your guys there.” The Editor mulled this over then offered, “You probably have Bar Mitzvah-level Hebrew. Not good enough here. But we have something called Ulpan, an intensive Hebrew language program for new immigrants. I can get you in. Once you speak like a native, I’ll toss you a few freelance assignments. If you write impressively, I might bring you on staff. But. And this is a non-negotiable but. I want you to return to college and get your degree. Here’s my card. When you get back to Israel with your diploma, call me.” I was so energized when I returned to school, I couldn’t wait for an opportunity to express everything I absorbed in Israel. That opportunity came when an English professor asked the class to write about a historic event. Perfect, I said to myself, I’ll write about the Six-Day War, not in boring prose, but in a dramatic, character-driven stage play, starring Israeli General Ariel Sharon, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, and, of course, the dashing, charismatic Moshe Dayan. I was utterly thrilled to turn in my stage play, but crestfallen when I received the written response from my professor, “Mr. Kott. You seem to have ignored the title of my course. Expository Writing. Writing that seeks to explain, not entertain. Scholarly writing. Textbook writing. You obviously took it upon yourself to change the title of my course to Dramatic Writing. Not a wise decision. Hence, you leave me no choice but to award you the only grade it deserves. F. By the way, this short but explanatory note to you is a fine example of Expository Writing.”

Please continue to: https://garykott.com/more-about/