More About Moms With Kids In Showbiz

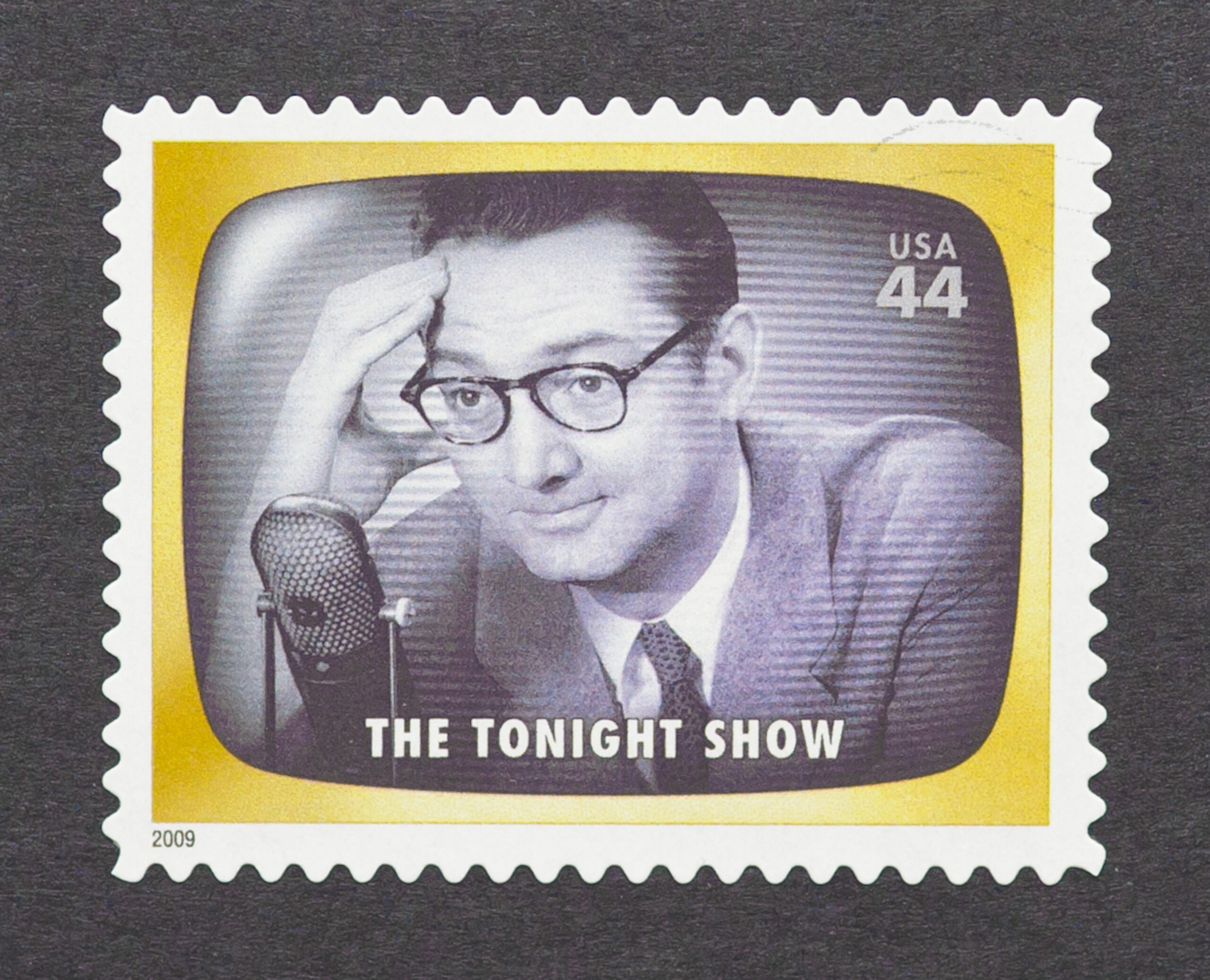

Me in the entertainment industry? I don’t get it. I can’t sing. I can’t dance. I don’t tell jokes. I acted in one play in my life in the fourth grade, the Pied Piper of Hamlin, and I only got that part because I knew how to play three notes on the recorder versus my casting rival Tommy Pikarski who played trumpet and you simply can’t have the Pied Paper playing a trumpet. Wait a minute. I was in another play. This one was when I was in college. I was Managing Editor of our school newspaper and it was my job to decide what stories needed to be covered and what reporters were going to cover them. I thought I was being fair in my story allotment, student government, sports, academics, until I received a nasty note from the head of our Drama Department complaining that the student newspaper hadn’t even included a blurb about their upcoming production of Arthur Kopit’s “Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feelin’ So Sad.” To make amends, I showed up at the campus theatre pen and pad in hand to cover the story myself. After interviewing the director and actors I said my goodbyes, only to be stopped at the door. The director had an idea. Wouldn’t the article be better if the reporter was actually in the play itself? Despite my protestations about having no acting experience the director claimed none was needed. There was one role in the play that would be perfect for me. Dad. Dead Dad. Hanging in the closet. Until, on cue, the closet door opens, and the corpse flops out onto the stage, shocking the stunned audience. No singing. No dancing. Just flop. Dead body. Bravo. Not much of a resume to end up in the entertainment industry. However, as I learned quickly in the real world, actors need dialogue to recite on stage, and instructions about which door to enter and which to exit, and plots, and beginnings, and middles, and ends and, lo and behold, my natural-born writing talents seemed quite adequate to provide all of the above. Now a professional scriptwriter, I found myself working on TV shows and stage plays with television stars, movie stars, Broadway stars, all studying scripts I’d written, memorizing lines I’d written, exiting through doors I’d written. My life was now engulfed by actors, singers, dancers, famous, soon-to-be-famous, at studios, at parties, phone calls, lunches, until one day I realized just how entrenched in the entertainment industry I’d become. “My god,” I said to myself, “My friends, my co-workers, are people other people pay to see.” When the abnormal becomes normal, years go by without ever noticing that working with celebrities was simply part of the job, show after show, same routine, write script, table reading, first rewrite, rehearsal, next rewrite, more rehearsal, camera blocking, tape night, live audience, wrap, start writing next week’s show. Then one day you’re snapped out of your complacency when someone walks onto the set that you just can’t believe you’re seeing live and in person. In my case it was this. I’d been hired to write for a television comedy with a cast of famous actors including glamorous Jayne Meadows, a movie star of the forties and fifties and an icon to people of my mother’s generation. However, for me, the main attraction of working with Jayne Meadows was meeting her husband, one of my childhood heroes, original host of The Tonight Show, the brilliant, inventive, hilariously funny Steve Allen. Every time he visited our set to view a taping, I was amazed when Steve Allen would walk over to me, offer compliments on a script that had my name on it, treat me as if we were equals in the world of comedy, which, of course, I wasn’t. After that show was cancelled, I never saw Steve Allen again, until one day I was invited with my two writing partners on a different show, to appear on his radio program in New York City. There we were in a booth, talking about comedy writing, the three of us and our host, Steve Allen. Dissolve several more years. I’m now living a quiet life in the country when my mother calls from Florida very excited. “Guess who’s coming to Sarasota?” My mother pauses dramatically before spilling, “Your old friend Jayne Meadows. She’s touring her one-woman show and my friends and I have orchestra seats.” I tried to convince my mother that not only wasn’t I friends with Jayne Meadows, but that she probably wouldn’t remember my name. “Nonsense,” my mother insisted, “Anybody who ever worked with you would remember.” On her way to the theatre, the other women in the car seemed to agree with me, “You claim your son worked with everyone in Hollywood. If you’re so confident that Jayne Meadows knows your son, why don’t you ask her during the Q&A?” And that’s precisely what my mother did, with a packed house filled with elderly but loyal fans of Jayne Meadows, my mother raised her hand and said, “My son once worked with you on a television show. He was a writer.” Jayne Meadows tried not to roll her eyes, having had a history with people claiming some sort of connection. Politely but suspiciously, Ms. Meadows inquired, “And what’s your son’s name?” To which my mother belted out, “Gary Kott.” To which Jayne Meadows belted back in front of a thousand awed audience members, “Gary Kott! I loved working with Gary Kott!” My mother stole a second to bask in her glory, preening before her dumb-struck friends, dumb-struck even more when Jayne Meadows added, “Now you tell Gary that when I get back to Los Angeles, Steve and I want him to come over to the house for dinner. Oh, Steve will be very excited. Don’t forget. Tell Gary to call us.” Possibly the crowning moment of my mother’s life; Jayne Meadows, in front of a theatre filled to capacity, inviting Gary Kott to the Steve Allen house for dinner. Unfortunately, my mother took that invitation so strongly to her heart, she never let me forget it. Every phone call we had thereafter, no matter what we’d talked about, ended with, “Did you call Jayne and Steve?” “No” “They really want you to come over for dinner.” A year later. Five years later, “Did you call Jayne and Steve?” Finally, after battling cancer, my mother was on her death bed. She was too sick to talk. But her dying eyes beseeched me, “Gary, son,” she spoke wordlessly, “Did you call Jayne and –” Before she could finish her sentence, my mother was gone.

Please continue to: https://garykott.com/more-about/