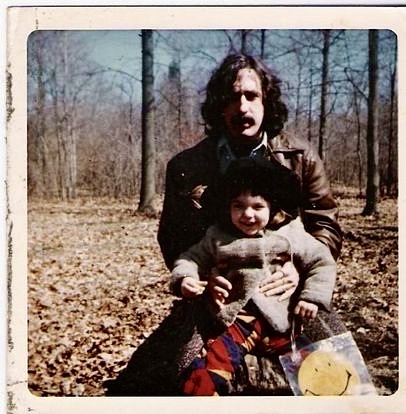

“New Joisey,” that’s how my grandfather pronounced the state I grew up in, a sound echoed when he addressed his son, my father, Bernard, aka Bernie, aka “Boiney.” My mother Marguerite, aka Mickey, had no such phonological aberrations, possessing perfect diction, wholly natural I thought until I met her sister and brother from Oklahoma, both speaking with such thick Okie accents I couldn’t understand a word they said, as my mother once sounded until she studied speech at the University of Michigan, removing any trace of her dust bowl origins. My parents settled in Cranford, New Jersey, exit 137 on the Garden State Parkway, exit numbers serving as an easy source of location, i.e. “What Exit?” “137,” New York City suburb versus, “102,” Jersey shore. My youthful years offered no clues that I was headed for a life in the creative world. I spent no time whatsoever drawing, or writing, or dreaming up stories. My days were devoted to mastering the lofty pursuits of a dedicated Jersey boy, stickball, stoopball, bowling, knucks, diners. I excelled in nothing at school save for one “good work” in Social Studies and, in the second grade, Best Cowboy Outfit. My poor mother, elected to the Board of Education, was brought into the high school Principal’s office and told “Don’t expect anything from your son in the future.” For a while those words seemed prescient. My academic performance at Marietta College was catastrophic. I was rarely seen in class, visible instead at the local pool hall, various bars, and numerous campus protest demonstrations. Years later, when I was invited back to Marietta to receive the Distinguished Alumnus Award, I was informed by an administrator that as a student I’d been one of the colossal reprobates in the history of the school. After graduation, I tramped to New York City with an abysmal transcript and a stack of newspaper articles I’d written for the school newspaper. Broke and jobless I scuffled from a run-down apartment off Needle Park to a transient hotel on 39th Street to a burned-out tenement on 83rd. I don’t remember one person saying about me, “Now there’s a young man that’s going to go far.” Most said, “Now there’s a young man doomed to failure.” Again, years later, in deference to success I had in Hollywood, my hometown newspaper sent a reporter to New York to interview me, local boy makes good. The reporter, a woman that never left town, remembered me from high school homeroom. She also remembered all the exceptional kids from our graduating class, athletes, academics, cheerleaders, school leaders, most singled out by teachers and fellow classmates as stars of tomorrow. The reporter, before beginning her interview, just stared at me, confused, baffled, before uttering her sentiments about my ascension to national acclaim, “Why you?”

My mother never got over it. That meeting with the high school principal and his message of doom about my future, lasered a permanent scar on my mother’s brain. It reached a point where decades later, even though I’d achieved career success from the time I was in my early twenties, my mother would go into a trance, “I sat in the principal’s office. Knowing that I was on the Board of Education, he measured his words carefully, ‘Mrs. Kott. I truly understand how important education is to you. Your work on behalf of our school system is admired by all. Certainly, your love for education was reflected in the performance of your daughter, Stefanie. One of the brightest students in her graduating class. And I hear she’s a Dean’s List student at the University of Pittsburgh. Which brings me to your son, Gary. A very nice boy to be sure. But a student? Well, you’ve seen his report cards. I’m sure what I’m about to say will come as no surprise. And this is not just my opinion. I’ve checked with all his teachers, and everyone seems to have come to the same opinion. Gary is simply not cut out for the rigors of higher education. College material? Let me put it this way. There are dozens of small schools in the country with low admissions policies. I am certain that there’s at least one that will accept him. The question is, why? Does a college degree guarantee happiness in life? There are plenty of careers out there for people like your son. Sales. Retail. Landscaping –‘” The horror in my mother’s eyes left me no choice but to snap her back to reality, “Mom, it’s me, your son, I won a Peabody Award.” My mother, Marguerite “Mickey” Kott, simply had no understanding of the concept of human failure. This was a person that morphed her way out of a tiny Oklahoma farm community, landed a reporting job on the New York Post when my father was in the army, hosted Eleanor Roosevelt for a day, interviewed Frank Sinatra in his prime, started her own theatre company after being rejected by the Cranford Drama Club because she was Jewish, was elected President of the PTA, then ran for office and won against six men vying for a seat on the Board of Education, became a representative for Scholastic Magazine, fought vigorously for civil rights, eventually boarding a bus and joining the March on Washington. Needless to say, my mother was apoplectic about my atrocious college performance, never once offering to come visit, not even on graduation day. However, my career? The biggest fan a boy could have. After my father died, my mother’s Florida condominium became a shrine to my accomplishments. Framed copies of newspaper articles on her walls. Framed photographs of awards I won. Then there were her private screenings. Every Thursday night during my five-year run on The Cosby Show, my mother would invite over a select group of friends to watch the newest episode. A few days later I’d receive Polaroids of the group cheering when they saw my name appear on the television screen. Things turned ugly when I announced to my mother that I would not be returning for a sixth season. Acutely aware of when my contract was up, she phoned to see if I’d signed on the dotted line. When I told her that I decided not to return to the show, she went deadly silent. She was well aware that I’d been working seven days a week for five years. She knew that the endless late hours had taken a ruinous toll on my body. I informed my mother about several appointments I had with my doctor. He was extremely concerned about my health. The doctor pulled no punches, “Gary, one more season and you’ll be dead.” My mother listened carefully, absorbing the grave consequences in returning to The Cosby Show, before uttering her motherly sentiments. “Gary,” she said decisively, “You can’t do this to me. I’m a celebrity down here.”

The best way to describe my relationship with my father is to quote my Hollywood agent when I vented to him about trouble I was having with the head of a studio I was under contract to. “Gary,” my agent stated, “With people it’s either a mesh or a non-mesh.” Non-mesh. There it is. A precise description of a lifelong struggle between two people that simply didn’t get along. Not that I didn’t try. From the time I can remember I bent over backward to earn at least one fatherly atta boy. At summer camp I won Best All-Around Camper. Not a mention from my father. I was selected to the Little League All-Star team. Not a mention. I won a high-game bowling trophy in my teen league. Zero. Grown now, I was hired by a prestigious New York advertising agency. My father never mentioned a thing. I was nominated for five Clio Awards in one year. Not a mention. I was promoted to Vice President/Creative Director. Still no atta boy. Switching careers, I wrote scripts for every major studio in Hollywood. Nothing from Dad. I received a Writers Guild of America Award, a People’s Choice Award. Not a peep. During all this, I wrote a novel and was signed by a leading New-York literary agent who was sending it to the most prestigious publishing houses. My father, a voracious reader, never asked to read my book until he reluctantly said yes when I brought him a copy. I never heard a word from him. Four months later, I visited my folks and asked my father, “Do you remember the book I handed to you?” He acknowledged, “Yes.” “Did you ever read it?” “Yes.” I screwed up my courage, “What did you think?” My father took a moment to formulate his review, then shrugged his shoulders, “Eh.” Then he walked away. A few years later, a friend, a well-known comedian, was headlining at an Atlantic City Hotel and Casino. Knowing about my troubled relationship with my father, he invited my parents to be his guest of honor at one of his performances. My parents, retired in a nearby seaside community, showed up, were treated royally, and during the performance, my friend the comedian introduced his honored guests and had the spotlight turned on them. My father never mentioned a word of it to me. I signed a movie deal with Universal. He never mentioned it. The Philadelphia Enquirer wrote a front-page article about me in their Sunday New Jersey Magazine Section, filled with quotes I offered about my amazing parents. Nothing from Dad. One day, I thought my moment in the sun had finally arrived. My father asked me to join him for a private talk. Thrilled with anticipation, I closed the door behind us. My father lost not a second, “Everyone tells me what a big success you are.” I stood there euphorically until he capped his statement, “I just don’t get it.” With nothing more to add, my father opened the door and walked out. He died later that year.

I’m not yet prepared to present an accurate portrayal of my sister Stefanie, from her wonderful beginning to her troubled middle to her tragic end.

Please contine to: https://garykott.com/more-about/