More About Dr. Albert Ellis

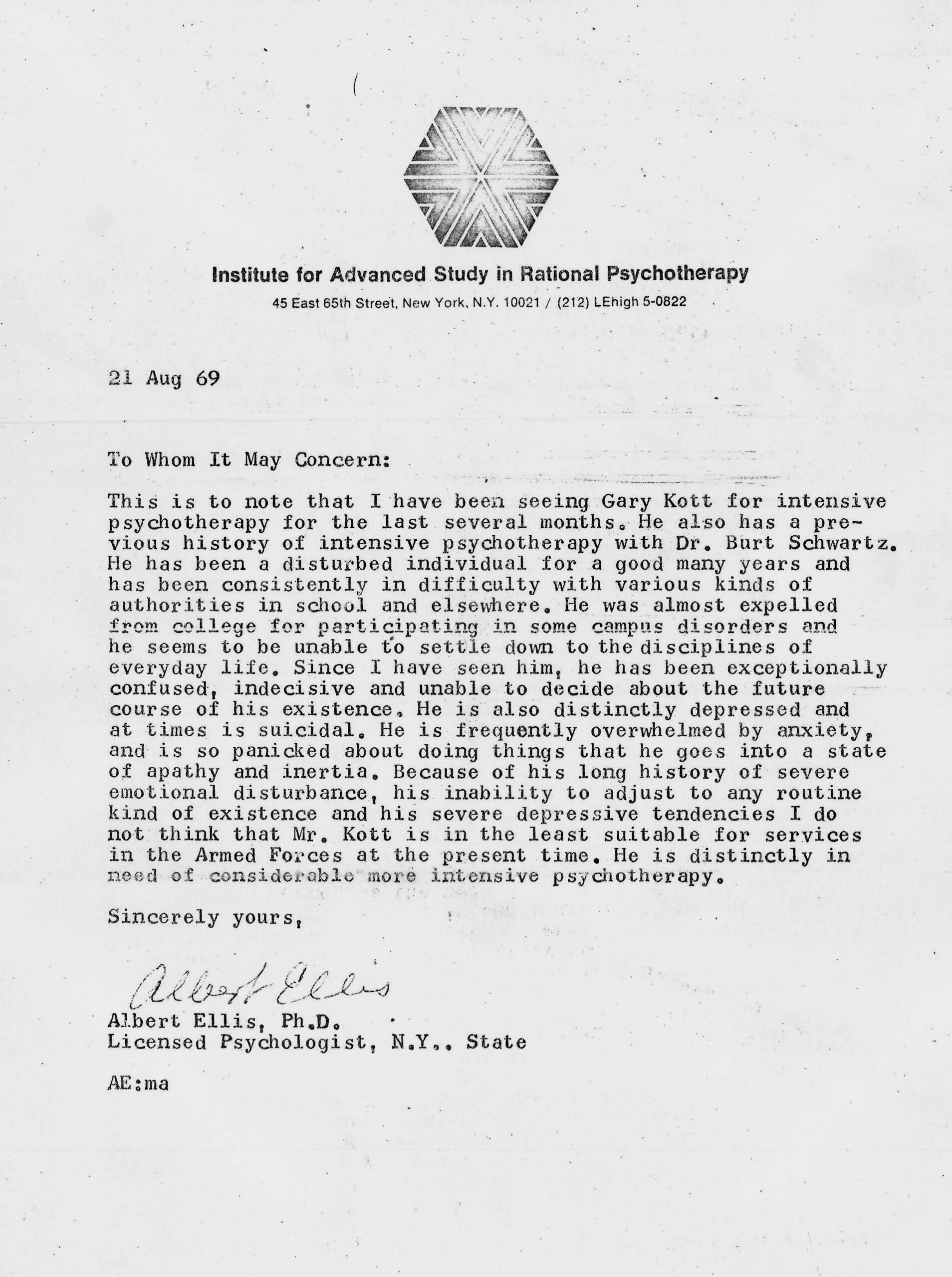

I was in the living room of a friend’s apartment, scanning her walls of bookshelves, neatly stacked and arranged in sections, much like a fine bookstore, fiction, non-fiction, travel, self-help, the latter being an area I had no experience with. I long-ago adopted the strategy of dealing with emotional pain and uncertainty by drinking them to death, and then, once I quit drinking, I embraced a hard-knock spiritual maxim not found in any book, “what is is, and what fucking is fucking is.” I was somewhat startled by my friend’s plethora of self-help titles, “Real Magic: Creating Miracles in Everyday Life,” “The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success,” “The Power of Now,” topics I had no interest to talk about and so I darted my eyes quickly to the next section of books, psychology, “The Interpretation of Dreams,” “Understanding Human Nature,” “Conditioned Reflexes,” an impressive array of classics I was on the verge of commenting about when my eyes caught sight of an entire shelf crammed with books written by a psychologist I knew very well. “Albert Ellis.” I muttered, “He’s my old shrink.” My friend asked, “Albert Ellis was your psychologist?” I answered, “Several times at different periods of my life.” She remarked, “And you just casually mention it? That’s like saying, ho-hum, Sigmund Freud’s my shrink.” She went on to tell me about a study that had come out a few years earlier. A professional survey of American and Canadian psychologists selected a list of the most influential psychotherapists in history. Carl Rogers came in first. Albert Ellis second. And third? Behind Albert Ellis? My friend delivered the startling conclusion, “Sigmund Freud.” I was impressed, but a bit preoccupied by the multitude of books she owned written by Ellis, “Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy,” “A Guide to Rational Living,” “How to Live with a Neurotic,” in addition to dozens of others that I’d never heard about including, “How to Stubbornly Refuse to Make Yourself Miserable About Anything: Yes, Anything!” I was exhausted just reading all the titles and could barely imagine how somebody could be so prolific. My friend, on the other hand, was fixated on the fact that I was a patient of Albert Ellis, “When did you first see him?” I reflected way back to an extremely screwed-up me and filled in the blanks, “In my junior year of college I was visiting my parents in New Jersey. They were having one of their family reunions called a ‘cousin’s club.’ Packed into our living room was a noisy group of aunts, uncles, cousins and second cousins, including a serious man, a psychiatrist, I had no idea had been observing me during the get-together. Towards the end of the evening, he approached and pulled me aside, “I’ve been watching you all day. The way you reacted every time your father drew near. It’s concerning. I’m not sure if you’re ready for this, but if you ever need help, here’s a number I want you to call. He’s a very good psychologist. We worked together early in his career.” He slipped me a piece of paper with the name and phone number of Albert Ellis. I folded the paper, slid it into my wallet and forgot about it for two years. After graduation from college, I sublet an apartment on 71st and Broadway in New York City, a high crime district in 1969 known for drugs and prostitution, the edge of Needle Park, where, in a fit of abject depression, I climbed out of my window onto the ledge eleven stories up, shuffled my feet towards the street below, wrote a long suicide note on a yellow pad, until my roommate entered the apartment and coaxed me inside to safety. The next morning, I remembered the piece of paper in my wallet with the name and phone number given to me at the family cousin’s club. I dialed, told the receptionist about the window ledge, was put on hold, and then instructed to be at the office at eleven and to bring the yellow pad with me. Dr. Ellis took one look at me, then read what I’d written, fixed his eyes on mine and said, “Son, you better keep writing.” I saw Dr. Ellis for quite some time, often not saying a word to him, as I’d walk into the room, sit and just stare at him in total silence, and he’d stare back at me until the fifty minutes were up then say, “See you next week.” Once he brought me to a night session and had me sit in with a group of patients from a mental hospital. About that time, I received from the Selective Service System my order to report for induction, and Dr. Ellis wrote the following letter to my draft board:

Once I was rejected for military service, I thanked Dr. Ellis for helping me, only to be soundly reprimanded at the suggestion that he would write a false letter to the United States military that could possibly jeopardize his license to practice psychotherapy. “Every word I wrote in that letter is true,” Dr. Ellis assured me. “You are an extremely disturbed individual.” Soon after, I buried my troubles in work, first as a professional writer on Madison Avenue and then in Hollywood. During my first career, I stopped seeing Dr. Ellis until I showed up at his office to discuss the ravages of my new marriage that I desperately wanted to save, despite the fact that I came home from work one evening to find that my wife had taken our son, all their belongings, and moved in with her parents. Nonetheless, I begged my wife to return and she did, a move that Dr. Ellis thought unsound on my part. He elaborated, “Your wife gave you the chance to correct a youthful mistake. You turned it down. I only hope that your future with her goes better than what I expect.” It didn’t. Our marriage was one of terrifying unhappiness that ended quite predictably in divorce. Years later, the day after I left my friend’s apartment, the one with the stacks of books, I acted on a whim and phoned The Institute for Rational Living, the now celebrated home of Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy, the legacy of Dr. Albert Ellis. I asked the receptionist if Dr. Ellis still saw patients. The receptionist explained no, but there were many qualified psychotherapists at the institute that might help me. I thanked her but declined, adding, “I was just curious. I wanted to say hello to Dr. Ellis. I’m a former patient.” She asked, “How long ago?” “1969. Forty years ago.” The receptionist put me on hold then came right back on, “He’ll see you in his office tomorrow at two.” Thus began a regular get-together that continued for over a year, me and ninety-year-old Dr. Albert Ellis sitting in his office piled high with papers, chatting about why I left Hollywood, crazy romances I got myself into and survived, the writer Albert Ellis curious about a play I wrote called “Him And His Last Night of Sanity.” Dr. Ellis read my play, wholeheartedly enjoyed it, reminisced about his failed attempts at writing fiction of this caliber, succeeding instead with nonfiction books on psychology. One day Dr. Ellis agreed to see my grown son to try to figure out why he never wanted to talk to me. My son arrived and Dr. Ellis asked him, “What’s the problem you have with your father?” My son, with an opportunity to open up, simply smiled and said, “I don’t have a problem.” A moment of silence. “Then I guess,” Dr. Ellis surmised pointing to me, “the problem is only within him.” My son wholeheartedly agreed, they shared a laugh, and our group therapy ended without a trace of understanding why to this day when I try to talk to my son he slams the phone down, leaving the eternal question, “Is the problem within me?”

Please continue to: https://garykott.com/more-about/